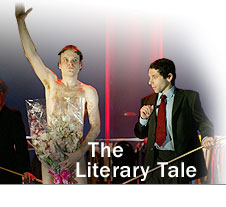

The Literary Tale Most folk and fairytales have their origins in primitive, preliterate culture; they are closely related to folk songs, ballads, proverbs, riddles, legends and similar orally-generated materials. During the nineteenth century, however, in response to the activities of collectors such as the Grimm brothers and Andrew Lang, many established writers including Ruskin, Browning, Thackeray, Dickens and Wilde in Britain, and Hans Christian Andersen in Denmark, began to compose tales as part of their literary output. Such tales shared many features with traditional oral tales, but they also differed in having many more descriptive passages, greater depth and complexity of characterisation, and much more specific times and places of action (few take place in the ‘once-upon-a-time’ characteristic of traditional tales). Also, because they were written down from the beginning, they have resisted the radical changes that have affected tales transmitted orally, which in many ways makes them less interesting. For instance, whatever version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Emperor's New Clothes you read, despite the vagaries of translation, the story is largely unchanged. The emperor is always male and foolish; he always processes naked, and a child invariably speaks out to the shame and confusion of those around him. Director Melly Still talks about how she went about the difficult task of choosing the stories that went into Beasts & Beauties . Today the value of traditional tales is widely understood. Perhaps their most powerful advocate has been Bruno Bettelheim who, in his book The Uses of Enchantment (extracts from which were posted up around the rehearsal room at the Bristol Old Vic), argued that they help children confront and resolve their fears and anxieties fictionally and, because they can be read, heard or watched over and over again, allow children to work through their problems and progress in the journey towards maturity. This, says Bettelheim, is why so many tales are concerned with separation, death, loss, and fears surrounding changing bodies. In Beasts & Beauties, ‘The Juniper Tree’ (see Part One and Two) is a good example. Carol Ann Duffy, who wrote the text on which Beasts and Beauties was based, belongs to a distinguished line of female retellers, including Ann Sexton, Angela Carter, Alison Lurie and Margaret Atwood. They bring out the hidden world of female experience contained in the tales, but also their humour, wit, and creative energy. This energy is not always directed against the male establishment: as Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of the foolish emperor and the wise child shows, the tales are prepared to question and poke fun at all those who presume to set themselves up as rulers and, in perhaps the most important message of all, to remind us that society is made by people. We get the rulers we deserve, the children we deserve, the parents we deserve – and the stories we deserve. This is why it is so important that each generation remakes the stories anew, perpetuating the process of metamorphosis on the one hand, and the transmission of deep knowledge on the other. |  | |